A pair of blood-spattered trousers in a miso tank and an allegedly forced confession helped send Iwao Hakamata to death row more than five decades ago.

Now, the world’s longest-serving death row convict has a chance to clear his name.

A Japanese court on Thursday is set to hand down its verdict in the retrial of 88-year-old Hakamata, who was sentenced to death in 1968 for murdering a family in a marathon legal saga that’s brought global scrutiny to Japan’s criminal justice system and fueled calls to abolish the death penalty in the country.

During the retrial, Hakamata’s lawyers argued new information proved his innocence, while prosecutors claimed there was enough evidence to confirm he should be hanged for the crime.

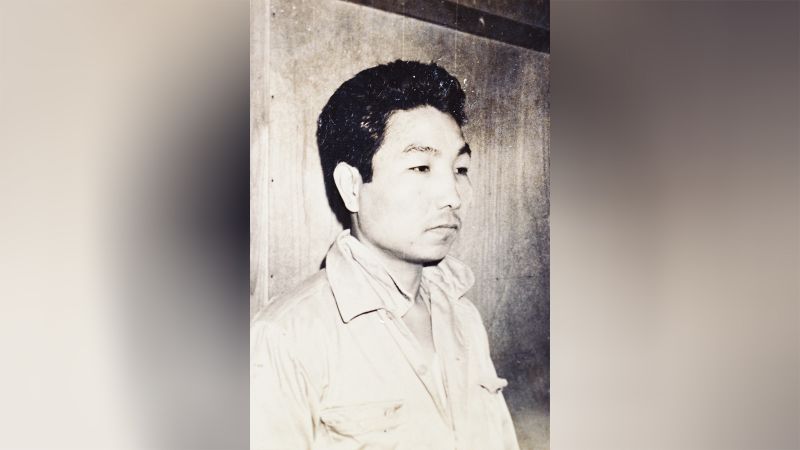

Once a professional boxer, Hakamata retired in 1961 and got a job at a soybean processing plant in Shizuoka, central Japan – a choice that would mar the rest of his life.

When Hakamata’s boss, his boss’s wife, and their two children were found stabbed to death in their home in June five years later, Hakamata, then a divorcée who also worked at a bar, became the police’s prime suspect.

After days of relentless questioning, Hakamata initially admitted to the charges against him, but later changed his plea, arguing police had forced him to confess by beating and threatening him.

He was sentenced to death in a 2-1 decision by judges, despite repeatedly alleging that the police had fabricated evidence. The one dissenting judge stepped down from the bar six months later, demoralized by his inability to stop the sentencing.

Hakamata, who has maintained his innocence ever since, would go on to spend more than half his life waiting to be hanged before new evidence led to his release a decade ago.

After a DNA test on blood found on the trousers revealed no match to Hakamata or the victims, the Shizuoka District Court ordered a retrial in 2014. Because of his age and fragile mental state, Hakamata was freed as he awaited his day in court.

The Tokyo High Court initially scrapped the request for a retrial for unknown reasons, but in 2023 agreed to grant Hakamata a second chance on an order from Japan’s Supreme Court.

Retrials are rare in Japan, where 99% of cases result in convictions, according to the Ministry of Justice website.

A justice system under scrutiny

Even as his case is closely watched around the world, a possible acquittal would not likely register with Hakamata, who after decades of imprisonment has seen a decline in his mental health, and is “living in his own world,” said his sister Hideko, 91, who has long campaigned for his innocence.

“Sometimes he smiles happily, but that’s when he’s in his delusion,” Hideko said. “We have not even discussed the trial with Iwao because of his inability to recognize reality.”

But for Hakamata’s supporters, the case is about much more than one man.

It has raised questions about Japan’s reliance on confessions to get convictions. And some say it’s one of the reasons why the country should do away with the death penalty.

“I’m against the death penalty,” Hideko said. “Convicts are also human beings.”

Japan is the only G7 country outside of the United States to retain capital punishment, though it did not perform any executions in 2023, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Hiroshi Ichikawa, a former prosecutor who was not involved in Hakamata’s case, said historically Japanese prosecutors have been encouraged to get confessions before looking for supporting evidence, even if it means threatening or manipulating defendants to get them to admit guilt.

An emphasis on confessions is what allows Japan to maintain such a high conviction rate, Ichikawa said, in a country where an acquittal can severely hurt a prosecutor’s career.

Japan’s Ministry of Justice said it could not comment on an ongoing case.

A long fight for exoneration

For 46 years, Hakamata was held behind bars after being convicted on the basis of the stained clothing and his confession, which he and his lawyers say was given under duress.

“The Japanese judicial system, especially at that time, was a system that allowed investigative agencies to take advantage of their surreptitious nature to commit illegal or investigative crimes,” Ogawa said.

Chiara Sangiorgio, Death Penalty Advisor at Amnesty International, said Hakamata’s case is “emblematic of the many issues with the criminal justice (system) in Japan” and that his conviction was “riddled with flaws and recognized as unreliable” by the fact that he was granted a retrial.

Death row prisoners in Japan are typically detained in solitary confinement with limited contact with the outside world, Sangiorgio said. Executions are “shrouded in secrecy” with little to no warning, and families and lawyers are usually notified only after the execution has taken place.

Despite his poor mental health, over the past decade, Hakamata has gotten to enjoy the small pleasures that come with living freely.

In February, he adopted two cats. “Iwao began to pay attention to the cats, worry about them, and take care of them, which was a big change,” Hideko said.

Every afternoon, a group of Hakamata’s supporters take him out for a drive, where Hideko says Hakamata “buys a large amount of pastries and juice.”

While Hakamata may not understand the significance of Thursday’s ruling, his family and throngs of supporters may finally see the world’s longest-serving death row prisoner declared innocent, once and for all.

“I hope he will continue to live a long and free life,” Hideko said.